The nation’s investor-owned electric utilities will attempt to deceive their customers into accepting new electric rate designs that would reduce people’s ability to save money by conserving energy or installing solar panels, according to a document describing the industry’s public relations plan obtained by UtilitySecrets.

The document is part of “The Lexicon Project,” a misinformation effort spearheaded by the utilities’ trade association, the Edison Electric Institute (EEI).

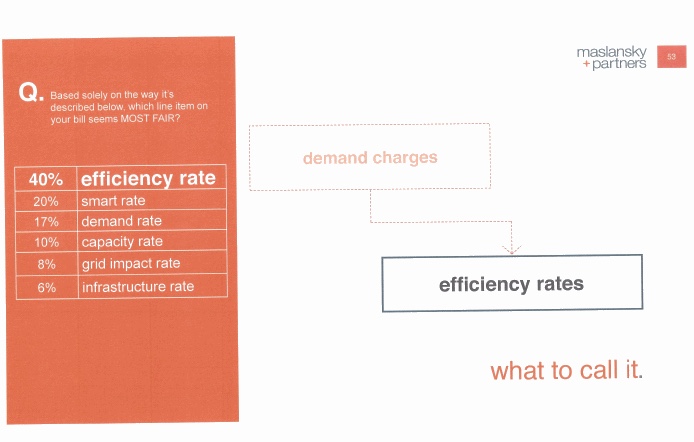

In the Lexicon’s latest edition, utilities outline their plan to rebrand “demand charges” as “efficiency rates.”

Residential demand charges: a new effort by utilities to claw back falling revenue

Families or small businesses may not understand why calling a “demand charge” an “efficiency rate” is misleading, because most will have never heard of a “demand charge” in the first place. Most electric customers generally pay two basic charges on their monthly bill: a “fixed charge” levies a fee for the cost of connecting the customer to the grid, and is the same every month. An “energy charge” is tied to how much electricity the customer uses; if the customer uses more, they pay more.

Utilities face the conundrum that they are increasingly collecting less money from customers as people and businesses become more efficient in their use of electricity and begin adopting rooftop solar power. Many utilities initially responded by trying to collect more money via fixed charges, but those efforts have proven politically unpopular, and have often been rebuffed by regulators.

Next, utilities attempted to introduce demand charges as a third charge for residential customers. Demand charges would charge customers based on the amount of electricity they use during one narrow window per month when they use the most electricity, often only 15 minutes or perhaps an hour long.

The utilities say that they would offset the new demand charges by lowering the “energy charges” customers pay, but those changes have big impacts.

Residential demand charges would harm energy efficiency, rooftop solar

Trying to rename demand charges as “efficiency rates” is especially perverse because demand charges do the exact opposite of what that name implies: they make it harder for customers to save money on their bills by employing energy efficiency or rooftop solar power.

Rooftop solar panels and energy efficiency technologies – like LED light bulbs or more efficient air conditioners – generally help customers save money by reducing the energy charge on their bill. When utilities reduce the energy charge portion of customers’ bills to make room for a demand charge, they reduce the incentive for customers to adopt those technologies. And rooftop solar panels or more efficient light bulbs may be unable to help reduce a customer’s 15 minutes of highest usage if they happen to turn on a bunch of appliances at once as kids are getting ready for school, or if a business gets a sudden rush of customers.

In a paper criticizing demand charges hosted by the Acadia Center, a pro-clean energy research organization, five experts in utility rates wrote that “these rate changes can significantly diminish the incentive for customers to reduce energy consumption through behavioral changes, energy efficiency technologies, or distributed generation resources and result in increased fossil fuel emissions.”

The study also warns that demand charges, like utility-backed efforts to raise fixed charges, could be regressive, harming low-income customers the worst.

“…low usage customers – including low-income customers – would likely pay more on average,” the study says.

For utilities, demand charges have the added bonus feature of kneecapping the economics of rooftop solar power, a technology that monopoly utilities have fought as a threat to their business model. One Arizona utility, the Salt River Project, installed a mandatory demand charge on all of its rooftop solar customers, a move that environmentalists and solar advocates charged was a naked effort by the utility to make rooftop solar less profitable for SRP customers.

If that was indeed the intention, it worked. One solar installer said it saw new installations plummet by 96 percent in SRP territory after the utility launched the charges.

Contrary to EEI Lexicon, demand charges take away customers’ control over their bills

Demand charges are not new for industrial customers, like factories, which are more sophisticated at monitoring their energy usage. Those companies often have software to know when they’re consuming too much power at once, risking a spike in their bill, and can use automated devices to react in real time to stop it.

The Lexicon instructs utilities to communicate demand charges to customers by “making it about how they are in control.”

But many residential and small business customers lack the data from their utility that provides the insight into their bill that factories might have, and some do not have any recourse even if they know a spike is coming.

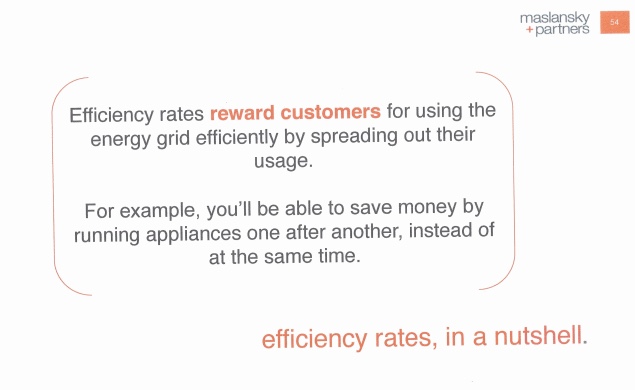

“Efficiency rates reward customers for using the energy grid efficiently by spreading out their usage,” the Lexicon instructs utilities to tell their customers. “For example, you’ll be able to save money by running appliances one after another, instead of at the same time.”

In practice, residential customers hit with mandatory demand charges have found them unpredictable and nearly impossible to control.

When a municipal utility in Kentucky tried to impose a mandatory demand charges to residential customers in 2016, the town grew outraged at the sudden unpredictability of their bills.

“If it hit during my busy season and during the right time of day, it would be a tremendous charge,” one small business owner said.

Kentucky’s Attorney General blasted the new rate:

“We are aware of customers who forgo a hot lunch, make their children sit in the dark, leave home to seek out relief, or who turn the air conditioning off on 90-degree days to avoid these excessive charges,” the letter read. The “rate structure is certainly a game changer for the people of Glasgow and there is no doubt the residents are the losers,” she said.

EEI’s effort to rebrand demand charges may stem from the fact that they have become politically unpopular in some places as well. When Commonwealth Edison, the Chicago utility and Exelon subsidiary, tried to shoehorn demand charges into an Illinois energy bill, the Governor’s office said in a memo that “the legislation as filed skyrockets energy prices for working families and fixed-income seniors through so-called ‘demand rates’ that would dramatically alter the way customers are charged for their energy usage. These are not demand rates, these are insane rates.” The demand charges did not make it into the final legislation.

One thing the Lexicon gets right: Time of Use Rates

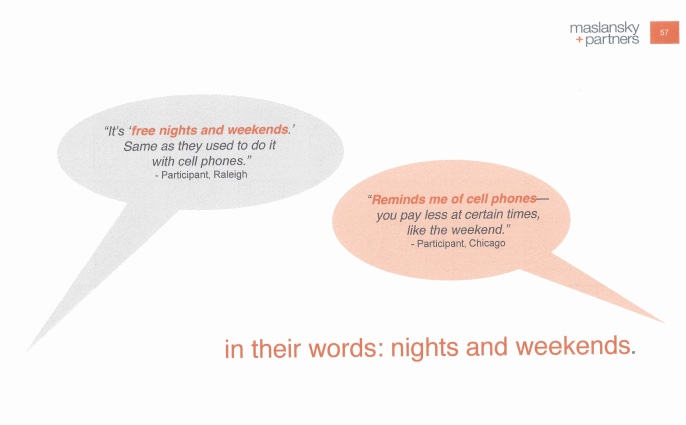

The EEI Lexicon is more accurate in the following section, where it suggests that utilities rebrand another rate structure, called “Time-of-use Rates” as “Peak and Off-Peak Rates.” Time-of-use rates charge customers more to use electricity during a designated block – say from five to nine p.m. – and less to use it during other times.

Most energy analysts agree that time-of-use rates hold far more promise to flatten out the peaks of electric demand – the times when the utility must fire up its most expensive power plants to produce enough electricity. Reducing those peaks would save money for all customers. Time-of-use rates are also easier for residential customers to understand and to use to save money.

EEI’s Lexicon instructs utilities to emphasize how time-of-use rates are “easy ways to reduce bills,” and provide “information that gives them confidence.” Unlike the Lexicon’s misleading description of demand charges, those talking points are broadly true, as proven by real-life examples some utilities know intimately.

In an Arizona rate case, the monopoly utility Arizona Public Service was trying to implement mandatory demand charges on its residential customers in 2017, while solar and energy efficiency advocates were instead proposing time-of-use rates. In the discovery phase of the case, APS was forced to present a study it had done of its residential customers who had signed up for demand charges as part of an optional (rather than mandatory) program.

APS concluded that “there is generally a low level of awareness among customers on a demand rate of their rate plan or the demand feature.” Instead, APS found that customers’ “ability to manage their energy cost is primarily from shifting energy usage to off-peak hours, leveraging the TOU [time of use] dimension of the plan … Customers are less confident about their ability to manage demand – with nearly half (49%) saying that they don’t know how to control demand or that it’s difficult.”

Utilities continue to misinform about solar energy and their track record with renewables

A consultant, Maslansky and Partners, is running the Lexicon effort for EEI. In his 2011 book, “The Language of Trust: Selling Ideas in a World of Skeptics,” Michael Maslansky boasted of his work to help “a major electric utility” sell its customers on an unpopular rate hike. He also recommended confronting utility customers with threats of “higher electricity rates” and “rolling blackouts” as a way to counter their enthusiasm for wind and solar power.

The latest version of the Lexicon re-emphasized talking points from previous presentations that showed utilities’ attempts to rebrand terms in ways that would mislead consumers about their relationship to solar energy.

- An early version of the Lexicon suggested that utilities attempt to rebrand utility-scale solar farms as “community solar” farms. After that effort was exposed and discredited, the companies settled on “universal” solar.

- Utilities continue to try to rename popular rooftop solar installations as “private” solar.

- Utilities are trying to rename “net metering,” a popular policy that ensures rooftop solar customers are fully compensated for the electricity they sell back to the grid, as “private solar credits.”

The lexicon also suggested that when utilities ask to raise their customers’ bills in proceedings known as “rate cases,” that they instead use the term “regulatory rate review” and emphasize that the cases are “a public process where independent state commissions determine energy rates.” (emphasis in original). That language seems to be an effort to tamp down the increasing concerns from customers and policymakers’ about regulatory capture.

The document also acknowledges some hard truths for the industry about customers’ perceptions of utilities. It notes that customers’ “truth” about their utilities’ record on clean energy is that the utilities “seem fundamentally opposed to it.” And that customers think utilities “should use more renewable energy and stop using fossil fuels.” If Maslansky’s findings are true, then utility customers are in fact quite astute: many utilities, like Florida Power & Light, are still over-investing in gas plants and pipelines, rather than moving wholesale into renewable energy, despite their rhetoric about being clean.

When politicians and utility regulators see terms like “universal solar,” “private solar,” and now “efficiency rates,” they should beware the spin. Customers should not have to suffer higher rates and less clean energy because the industry’s PR campaign fooled their elected officials and regulators.